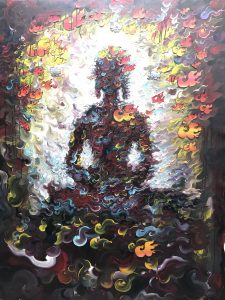

Our Moving into Meditation class explored what it means to live with a trusting heart. We drew inspiration from Jack Kornfield’s book, No Time Like the Present: Finding Freedom, Love and Joy Right Where You Are. In Chapter 5, Fear of Freedom. In this chapter, Jack explores the various ways our fears curtail our freedom and full engagement with life. He suggests that we can use loving awareness as a way of cultivating the courage and inner stability we need to take chances and embrace life fully.

Our Moving into Meditation class explored what it means to live with a trusting heart. We drew inspiration from Jack Kornfield’s book, No Time Like the Present: Finding Freedom, Love and Joy Right Where You Are. In Chapter 5, Fear of Freedom. In this chapter, Jack explores the various ways our fears curtail our freedom and full engagement with life. He suggests that we can use loving awareness as a way of cultivating the courage and inner stability we need to take chances and embrace life fully.

We also explored poet Jane Hirshfield’s views about creativity and mediation as outlined in her Tricycle Magazine interview, Felt in its Fullness. Jane asserts that art and meditation are both awareness practices that are essential to personal transformation.

Guided Relaxation

Welcome . . . Feel yourself arriving . . . feel your breath in its fullness . . . exploring and sensing the play of space between your senses and the air . . . inviting you to this now . . .  relaxed and aware. . . . each breath so wholly new . . . Allow your awareness to travel with sensation . . . tune in to the now of this area . . . each sensation continually changing . . . Become aware of any emotions and mind states you may be experiencing . . . . Giving them full attention . . . experience them fully . . . You could even name anything that rises up strongly . . . Name whatever feeling arises and holding it in loving awareness. Tender, loving, kindness. . . . Tune into the undercurrent of vulnerability that flows and moves through being . . . Give yourself this kind attention and open to what is true for you in this now . . . Drawing on inner wisdom. Allow yourself to trust in this moment, this life unfolding . . . Courage . . . wisdom . . . meeting currents of vulnerability . . . experiencing what it is to be fully human . . . and what it is to be free . . .

relaxed and aware. . . . each breath so wholly new . . . Allow your awareness to travel with sensation . . . tune in to the now of this area . . . each sensation continually changing . . . Become aware of any emotions and mind states you may be experiencing . . . . Giving them full attention . . . experience them fully . . . You could even name anything that rises up strongly . . . Name whatever feeling arises and holding it in loving awareness. Tender, loving, kindness. . . . Tune into the undercurrent of vulnerability that flows and moves through being . . . Give yourself this kind attention and open to what is true for you in this now . . . Drawing on inner wisdom. Allow yourself to trust in this moment, this life unfolding . . . Courage . . . wisdom . . . meeting currents of vulnerability . . . experiencing what it is to be fully human . . . and what it is to be free . . .

The joy of freedom arises with the fear of the unknown . . . venturing out of familiar grounds . . . habits . . . ways of thinking . . . countered by strong survival instincts . . . early conditioning. This powerful inner conflict surfaces as fear . . . in our bodies, hearts and minds . . . Painful early experiences may linger even while unconscious. We avoid life experiences that evoke our past hurts. We withdraw from activities that conflict with long held beliefs. We close ourselves off from relationships that challenge our perceptions and views.

Our unconscious fears live on to limit our full engagement with life. We bring loving awareness to those places we feel fear and pain and to those places we feel calm, strong and constant. We can find healing in those inner spaces of stability. We start where we are and how we feel . . . our breathing . . . our feet, hips and pelvis . . . the long curve of our backs . . . our shoulders, arms and hands . . . . our beating hearts . . . As we gradually feel emotions and hear the stories of past hurts we learn what our lives have to teach us. We can venture into new experience through the openings we create and the freedom we claim . . . We can draw on deep taproots and bring up the energy of creative expression . . . our offering to the world.

Our unconscious fears live on to limit our full engagement with life. We bring loving awareness to those places we feel fear and pain and to those places we feel calm, strong and constant. We can find healing in those inner spaces of stability. We start where we are and how we feel . . . our breathing . . . our feet, hips and pelvis . . . the long curve of our backs . . . our shoulders, arms and hands . . . . our beating hearts . . . As we gradually feel emotions and hear the stories of past hurts we learn what our lives have to teach us. We can venture into new experience through the openings we create and the freedom we claim . . . We can draw on deep taproots and bring up the energy of creative expression . . . our offering to the world.

In her book Ten Windows, poet Jane Hirshfield writes:

It is by suffering’s presence that we know there is something we need to address. [She believes that our] “suffering leads us to beauty the way thirst leads us to water. . . .

We make art . . . partly because our lives are ungraspable, uncarryable, impossible to navigate without it. Even our joys are vanishing things, subject to transience. How, then, could there be any beauty without some awareness of loss, of suffering?

We make art . . . partly because our lives are ungraspable, uncarryable, impossible to navigate without it. Even our joys are vanishing things, subject to transience. How, then, could there be any beauty without some awareness of loss, of suffering?

. . . In the midst of suffering, we almost have no choice. We have to feel and acknowledge it. It demands response. Art offers a way not only to face grief, face pain, but also to soften grief’s and pain’s faces, which turn back toward us, listening in turn, when we speak to them in the language of story and music and image.

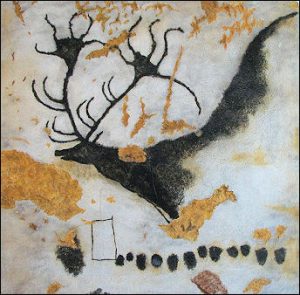

Jane believes our creativity allows us to accept suffering, to accept what actually is and then further our experience with something transformational – something that opens our hearts and minds. She acknowledges the futility of trying to run or hide from life’s challenges and hurts. Our innate creativity is like a portal through which we move more deeply into life and allow ourselves to be changed, to be touched and in turn we have the potential to change and touch others.

Creativity and meditation are both paths of awareness that allow us to move more deeply into feeling and to enter the fullness of our humanity. She writes:

. . . Awareness, whether in practice or art, asks a question: “What is worth paying attention to right now?” That could be my personal life. It could also be some larger question, shared by all. The questions of political intransigence, . . . and violence; the questions of the unfolding environmental catastrophe we are living within . . . Awareness is always the starting place. Awareness shows us the questions, the problems we might be able to solve and the questions that can’t be answered at all, and awareness makes the hand-holds and toe-holds appear, as we traverse the cliff of our lives. . . . “

. . . Awareness, whether in practice or art, asks a question: “What is worth paying attention to right now?” That could be my personal life. It could also be some larger question, shared by all. The questions of political intransigence, . . . and violence; the questions of the unfolding environmental catastrophe we are living within . . . Awareness is always the starting place. Awareness shows us the questions, the problems we might be able to solve and the questions that can’t be answered at all, and awareness makes the hand-holds and toe-holds appear, as we traverse the cliff of our lives. . . . “

In deeply attending we are open, we are vulnerable, so that we may discover what’s inside . . . our bodies, our memories, our imaginings and what’s outside . . . those worldly things that shape our bodies, evoke thought and engage response. Creativity draws from inside and outside in a dancing collaboration with life. Here is Jane’s poem, My Skeleton:

My skeleton,

who once ached

with your own growing larger

are now,

each year

imperceptibly smaller,

lighter,

absorbed by your own

concentration.

When I danced,

you danced.

When you broke,

I.

And so it was lying down,

walking,

climbing the tiring stairs.

Your jaws. My bread.

Someday you,

Someday you,

what is left of you,

will be flensed of this marriage.

Angular wristbone’s arthritis,

cracked harp of ribcage,

blunt of heel,

opened bowl of the skull,

twin platters of pelvis—

each of you will leave me behind,

at last serene.

What did I know of your days,

your nights,

I who held you all my life

inside my hands

and thought they were empty?

You who held me all your life

in your hands

as a new mother holds

her own unblanketed child,

not thinking at all.

Right now we can open ourselves to be touched by these words that tell of our shared human experience . . . the sweet, sad suchness that we call come to know when we are aware and open. And what comes of these awarenesses? These openings? What are you attending to in your life? What fields are you planting with your creative seeds? Our practice enables us to create those conditions in which our offerings might grow and be shared.

How do you satisfy the hunger to know your self? To know the world? In mindfulness practice we can experience these questions in profound and simple ways. We can be present for ordinary magic in life. We enter states of presence over and over again – presence is so much vaster than what we can grasp and hold. Like breathing . . . we have to let one breath go in order to receive the next. We live our lives in moments. In describing meditation Jane writes:

How do you satisfy the hunger to know your self? To know the world? In mindfulness practice we can experience these questions in profound and simple ways. We can be present for ordinary magic in life. We enter states of presence over and over again – presence is so much vaster than what we can grasp and hold. Like breathing . . . we have to let one breath go in order to receive the next. We live our lives in moments. In describing meditation Jane writes:

One breath leads to another. Some breaths are transparent, some are filled with silent weeping. Some tremble on the cusp of disappearance, others become the sound of cars or birds. Closely attended, any moment is boundless and always changing. You emerge from these kinds of undoing awareness and you know it is not you yourself who are all-important. You know something of the notes of your own scale . . . for me the most sacred thing is the most ordinary one, felt in its fullness.