The Yogabliss on-line Moving into Meditation class met this morning. We create our circle in a “virtual” space. In physics the term “virtual” refers to particles or interactions with extremely short lifetimes and indefinitely great energies. This makes me think of our own short lifetimes and interactions and the energy that we bring to creating the reality we all share. This “virtuality” is both a metaphor and one of the many paradoxes that we are living today. We are at once separate and together. We spend much of our time in digital territories and yet we are physical beings. We are body-heart-minds. We are animals. We are elemental beings. Our survival depends on nature – and nature’s survival depends on us.

The Yogabliss on-line Moving into Meditation class met this morning. We create our circle in a “virtual” space. In physics the term “virtual” refers to particles or interactions with extremely short lifetimes and indefinitely great energies. This makes me think of our own short lifetimes and interactions and the energy that we bring to creating the reality we all share. This “virtuality” is both a metaphor and one of the many paradoxes that we are living today. We are at once separate and together. We spend much of our time in digital territories and yet we are physical beings. We are body-heart-minds. We are animals. We are elemental beings. Our survival depends on nature – and nature’s survival depends on us.

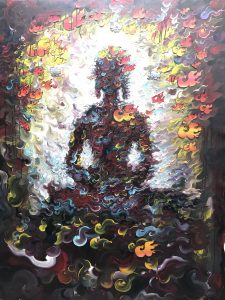

Today we practiced a body centered mediation around the classical elements of earth, fire, water and air. It is an ancient meditation that has been found in traditions across cultures around the world. It is a way of affirming and realizing ourselves as nature. You can find more about this meditation by going to Tricycle Magazine’s four part series, Mindfulness of the Four Elements: Reconnecting with the World, with meditation instructor and author Sebene Selassie.

Our reflection was inspired by Michael McCarthy’s interview, Nature, Joy, and Human Becoming, and his book, The The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy. Michael is a naturalist and writer whose work calls us to bring our love and joy to the defense of nature. He and poet Denise Levertov remind us that we are, ourselves, nature.

Our reflection was inspired by Michael McCarthy’s interview, Nature, Joy, and Human Becoming, and his book, The The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy. Michael is a naturalist and writer whose work calls us to bring our love and joy to the defense of nature. He and poet Denise Levertov remind us that we are, ourselves, nature.

In exploring the depth of our caring for ourselves, each other and the natural world we drew on the teachings of Roshi Joan Halifax. Her article, Discovery at the Edge of Empathy, and her book, Standing at the Edge: Finding Freedom Where Fear and Courage Meet, explore how we can work skillfully with deep empathy by tempering our emotions with mindfulness and compassion.

Guided Reflection

Environmentalist and writer, Rachel Carson, seems to affirm this elemental practice when she wrote:

Our origins are of the earth. And so there is in us a deeply seated response to the natural universe, which is part of our humanity.

In his On Being interview, Nature, Joy, and Human Becoming, naturalist and writer, Michael McCarthy says:

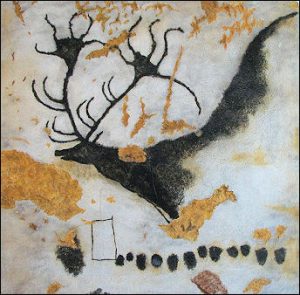

There is a legacy deep within us, a legacy of instinct, a legacy of inherited feelings, which may lie very deep in the tissues — it may lie underneath all the parts of civilization which we are so familiar with on a daily basis, but it has not gone; that we might have left the natural world, most of us, but the natural world has not left us.

There is a legacy deep within us, a legacy of instinct, a legacy of inherited feelings, which may lie very deep in the tissues — it may lie underneath all the parts of civilization which we are so familiar with on a daily basis, but it has not gone; that we might have left the natural world, most of us, but the natural world has not left us.

And here we are today living with the consequences of our shared history. All of us have been touched by the lingering pandemic, the painful manifestations of racial injustice, everpresent economic inequality, growing social polarization and enviromental degradation. It seems as though the earth is bearing witness to our tumult. These are challenges that we are facing together with the earth. While we are still breathing, we have the chance to rediscover our deep belonging with the Earth. And we can act to sustain what we hold so dear.

In his book, The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy, Michael writes about the 500 generations of civilization and the 50,000 generations when we were part of nature:

. . . where we evolved; where we became what we are, where we learned to feel and react . . . where the human imagination formed . . .

Perhaps you got a sense of this in your sitting practice this morning . . . those generations that live on inside you . . . the living strands of DNA . . . life’s coded instructions inside of us and most other organisms. We are “re-membering” as in bringing parts of ourselves back together again in the wholeness of our embodied awareness.

Perhaps you got a sense of this in your sitting practice this morning . . . those generations that live on inside you . . . the living strands of DNA . . . life’s coded instructions inside of us and most other organisms. We are “re-membering” as in bringing parts of ourselves back together again in the wholeness of our embodied awareness.

We are animal beings yet we may be one of the only creatures on earth so out of sync with nature. We live in temperature controlled boxes that are often lit deep into the night. We eat out of season foods grown far from where we live. Our resting and sleeping time is often cut short by the stress of our society’s demands.

Meditation instructor, Sebene Selassie, suggests that this element practice can help us “become more intimate with our visceral experience with our bodies . . . to notice what feels out of sync or out of balance with the elements in your life and around you.” When we are lost in thought or in the trance-like busyness of our lives we can:

. . . remember to ground in the earth of the body. We remember to feel the fluidity of the body. We remember to experience the fluctuations of temperature in the body through fire. Or we remember to experience the movement of air. . . .

. . . remember to ground in the earth of the body. We remember to feel the fluidity of the body. We remember to experience the fluctuations of temperature in the body through fire. Or we remember to experience the movement of air. . . .

Just as we find ourselves out-of-balance, our mindfulness practice can help us to recognize how these inner imbalances manifest in our natural world. As we exhaust ourselves we also exhaust our natural world. And yet, so much of our creative spirit and imagination call out for appreciation, conservation and restoration. Writer and earth advocate Ursula K. Le Guin urged us:

to use the world well, to be able to stop wasting it and our time in it, we need to relearn our being in it . . .

In the Moth Snowstorm, Michael McCarthy calls on the other elements of our human being to help heal what we have wounded so deeply – he calls for our love and our joy in this passage:

It is time for a different, formal defence of nature. We should offer up not just the notion of being sensible and responsible about it, which is sustainable development, nor the notion of its mammoth utilitarian and financial value, which is ecosystem services, but a third way, something different entirely: we should offer up what it means to our spirits; the love of it. We should offer up its joy.

Can our inner resources of love and joy move us to replenish that which we have exhausted? Can we help to heal that which we have wounded? Right now we can reflect on who and what we love. We can recall the last experience of awe, reverence or wonder. . . . Can there be a state of love, awe, reverence or wonder outside relationship?

Can our inner resources of love and joy move us to replenish that which we have exhausted? Can we help to heal that which we have wounded? Right now we can reflect on who and what we love. We can recall the last experience of awe, reverence or wonder. . . . Can there be a state of love, awe, reverence or wonder outside relationship?

Can we tap into that deep legacy of instinct and inherited feelings – under the layers of civilization – to love and care for our natural world?

Michael responds to these questions in saying:

. . . that if we could mobilize this sort of love we have for the natural world — and the essence of it is the fact that the natural world is a part of us, and that if we lose it, we cannot be fully who we are. And if we were to realize that, which is hard, and if we were to realize it on a large scale, which is even harder, that might offer a defense of nature . . .

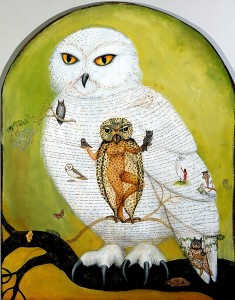

We feel the pain of others. This is part of our inherited legacy: the human gift of empathy. When we grieve for what has been lost, what we are losing – this is elemental being. In her article, Discovery at the Edge of Empathy, Roshi Joan Halifax writes:

Perhaps we don’t slip into the skin of others so much as we invite others to inhabit us, to slip into our skin, into our heart, thus making ourselves bigger beyond even our imagining. Empathy is not only a way to come alongside suffering in our small boat, it is a way to become the ocean. I believe that the gift of empathy makes us larger—if we don’t drown in the waters of suffering. And empathy that is alchemized through the medium of our wisdom gives us the energy to act selflessly on behalf of others.

Perhaps we don’t slip into the skin of others so much as we invite others to inhabit us, to slip into our skin, into our heart, thus making ourselves bigger beyond even our imagining. Empathy is not only a way to come alongside suffering in our small boat, it is a way to become the ocean. I believe that the gift of empathy makes us larger—if we don’t drown in the waters of suffering. And empathy that is alchemized through the medium of our wisdom gives us the energy to act selflessly on behalf of others.

In her book, Standing at the Edge: Finding Freedom Where Fear and Courage Meet, Roshi describes this wisdom as being born in compassion. She writes from the experience of drowning in empathy and from emerging from those waters through her years long mindfulness practice. Research has shown one of the benefits of meditation is an ability to shift from moments of empathic distress into equanimity and compassion. This capacity can facilitate the shift from brief moments of empathic distress into equanimity and compassion. Roshi Joan offers this encouragement:

If we fall over the edge, and we will sometimes, all is not lost. Empathic distress might serve as an instigating force that pushes us into compassionate action to end the suffering of others and ourselves. We need some degree of arousal, some level of discomfort, in order to mobilize our compassion. We just need to be sure we don’t get stuck in the swamp of distress, because it can drive us away from caring for others. If we can learn to distinguish self from other, without creating too much distance between them and us, empathy will be our ally as we serve.

I would add that the others Roshi speaks of includes our earth home and all nature. We can invite them “ to slip into our skin, into our heart.”

Michael describes how nature moves us so deeply:

. . . [I]t’s certainly the case that the reawakening of the world every spring is something that stirs very, very profound emotions in us. The fact that our lives are linear, they only go in one direction — but the life of the earth is circular; it goes round, and everything dies in the autumn, and the leaves fall off the trees, and the world seems to come to an end, and it’s locked up in ice, but then, it’s reborn. And that’s one of the greatest things in our lives, surely, that rebirth of the Earth. . . . And it’s not just the physical beauty, which is enormous; it’s the sense of new life, to us who only have one life, especially as we get older and we know that the end of it is coming; the fact that here is new life being born. I have a friend who’s a woodland scientist. He’s in his early 70s. And he said to me, last year, “I just see life now as how many springs I’ve got left.”

. . . [I]t’s certainly the case that the reawakening of the world every spring is something that stirs very, very profound emotions in us. The fact that our lives are linear, they only go in one direction — but the life of the earth is circular; it goes round, and everything dies in the autumn, and the leaves fall off the trees, and the world seems to come to an end, and it’s locked up in ice, but then, it’s reborn. And that’s one of the greatest things in our lives, surely, that rebirth of the Earth. . . . And it’s not just the physical beauty, which is enormous; it’s the sense of new life, to us who only have one life, especially as we get older and we know that the end of it is coming; the fact that here is new life being born. I have a friend who’s a woodland scientist. He’s in his early 70s. And he said to me, last year, “I just see life now as how many springs I’ve got left.”

Every day we might ask ourselves what matters most in the Springs we have left?

Poet Denise Levertov’s poem, Sojourns in the Parallel World, seems to respond:

We live our lives of human passions,

cruelties, dreams, concepts,

crimes and the exercise of virtue

in and beside a world devoid

of our preoccupations, free

from apprehension—though affected,

certainly, by our actions. A world

parallel to our own though overlapping.

We call it “Nature”; only reluctantly

We call it “Nature”; only reluctantly

admitting ourselves to be “Nature” too.

Whenever we lose track of our own obsessions,

our self-concerns, because we drift for a minute,

an hour even, of pure (almost pure)

response to that insouciant life:

cloud, bird, fox, the flow of light, the dancing

pilgrimage of water, vast stillness

of spellbound ephemerae on a lit windowpane,

animal voices, mineral hum, wind

conversing with rain, ocean with rock, stuttering

of fire to coal—then something tethered

in us, hobbled like a donkey on its patch

of gnawed grass and thistles, breaks free.

No one discovers

just where we’ve been, when we’re caught up again

into our own sphere (where we must

return, indeed, to evolve our destinies)

—but we have changed, a little.