Last Saturday JT, Ethnobotany Guide Extraordinaire, lead us, ethnobots, on a foraging walkabout around the Seattle Jackson Place, Judkins Park and International District. She made it fun by challenging us to a scavenger hunt. She interwove plant observations along with the multi-cultural stories of the people who made their homes here. This was a powerful learning about place: Seattle is home to many cultures; it has a history of discrimination and displacement. Sort of like the plants that end up here – they are blown in from the wind or carried by birds. Some of those winds are the harsh forces of conflict in home countries. Immigrants and refugees take root and are then uprooted again by powerful economic and social forces.

Last Saturday JT, Ethnobotany Guide Extraordinaire, lead us, ethnobots, on a foraging walkabout around the Seattle Jackson Place, Judkins Park and International District. She made it fun by challenging us to a scavenger hunt. She interwove plant observations along with the multi-cultural stories of the people who made their homes here. This was a powerful learning about place: Seattle is home to many cultures; it has a history of discrimination and displacement. Sort of like the plants that end up here – they are blown in from the wind or carried by birds. Some of those winds are the harsh forces of conflict in home countries. Immigrants and refugees take root and are then uprooted again by powerful economic and social forces.

Plants and people grow toward light. We all want to flourish and enjoy the fruits of our labors. These fruits can be seen in the Central District neighborhood homes, churches and temples, community centers, gardens and parks. Native and ornamental plantings were everywhere – adorning yards and also breaking through the cracks in the sidewalks. We began our walkabout in JT’s neighborhood, once predominantly Italian American. We hunted herbs for the heart, liver and mind.

Hawthorn is a tree in the rose family that grows all over the Northern Hemisphere. Its high favonoid content has been shown to decrease inflammation and oxidative stress. Hawthorn has helped to reduce heart problems including high blood pressure and improve heart function.  Fall berries can be made into honeys and jams. “Hearty” Hawthorn seems at home in the city. I discovered it just a few years ago when coming upon some Russian emigres picking red berries on the Snoqualmie River. They explained that the berries were “very strong heart medicine.”

Fall berries can be made into honeys and jams. “Hearty” Hawthorn seems at home in the city. I discovered it just a few years ago when coming upon some Russian emigres picking red berries on the Snoqualmie River. They explained that the berries were “very strong heart medicine.”

Dandelions have long been used by herbalists to support liver health. Roots can be boiled to make a decoction or dried and roasted to make a fine tea. Flowers and leaves are edible.  I’ve experimented with greens in salads, pestos and soups. Last week we enjoyed dandelion blossom shortbread cookies. Gather the blossoms in the sun and it will bring happiness.

I’ve experimented with greens in salads, pestos and soups. Last week we enjoyed dandelion blossom shortbread cookies. Gather the blossoms in the sun and it will bring happiness.

Rosemary is a member of the mint family which includes many other herbs, such as oregano, thyme, basil, and lavender. Rosemary is rich in anti-oxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, which are thought to help boost the immune system and improve blood circulation.

Scientists have found that rosemary may also be good for your brain. Rosemary contains an ingredient called carnosic acid, which can fight off damage by free radicals in the brain. Some studies have suggested that rosemary may significantly help prevent brain aging. Research continues on rosemary’s possible uses in treating Alzheimers.

We walked through Jackson Place area where JT pointed out a magical Ume tree. Ume plum trees date back to the late 1930s when Japanese immigrants may may have planted them. Plum tree blossoms celebrate Spring. JT shared its preserved  fruits in several forms: umeboshi, a salt-preserved plum, Li Hing as hard salted plum snack and powder. Umeboshi is used as a traditional condiment and also considered a digestive aid. Green ume extract is used as a tonic in Japan. The Japanese plum originated in China. Li Hing Mui means traveling plum.

fruits in several forms: umeboshi, a salt-preserved plum, Li Hing as hard salted plum snack and powder. Umeboshi is used as a traditional condiment and also considered a digestive aid. Green ume extract is used as a tonic in Japan. The Japanese plum originated in China. Li Hing Mui means traveling plum.

The Chinese and Japanese cultures and histories are interwoven through Seattle neighborhoods: in homes, churches, temples, gardens and parks. We walked past the Konko Church – a faith originating in Shinto nature worship.

Walking down King Street we entered Chua Viet Nam. This was the first Vietnamese Buddhist temple established in Washington in 1978. In the mid ’70s Vietnamese immigrants came to Seattle after the fall of Saigon to escape persecution and violence in their war-torn country. The first wave of people were housed in Camp Murray. Eventually they built businesses and community clustered around Little Saigon, just east of the International District.

Walking down King Street we entered Chua Viet Nam. This was the first Vietnamese Buddhist temple established in Washington in 1978. In the mid ’70s Vietnamese immigrants came to Seattle after the fall of Saigon to escape persecution and violence in their war-torn country. The first wave of people were housed in Camp Murray. Eventually they built businesses and community clustered around Little Saigon, just east of the International District.

Walking through the temple garden I was moved by the beauty of the plantings that surrounded statues of the Buddha and Quan Am, the bodhisattva of compassion. Carefully placed offerings of fruit, flowers and incense reflected the value of gratitude. A common saying is: “Eat the fruit, remember who planted the tree. Drink the water, remember the source.”

As we continued toward Yesler Way we passed a Western Red Cedar. This was “tree of life” to northwest tribes who considered themselves the “people of the red cedar.” JT explained the importance of the tree to the indigenous people of what is now Seattle. This tree touched every aspect of native peoples’ lives. The wood was used for housing, utensils, boxes, boards, instruments, canoes, vessels, and ceremonial objects. Western Red Cedar is also associated with a long tradition of curing and cooking fish over the open fire. Roots and bark are used for baskets, bowls, ropes, clothing, blankets, and rings.

Duwamish people have been living in the Seattle Metropolitan area for 10,000 years. They were displaced from their homeland by European settlers. The current Duwamish tribe organized in the aftermath of the Treaty of Point Elliott in the 1850s. Although not recognized by the U.S. federal government, the Duwamish remain an organized tribe with roughly 500 enrolled members as of 2004. In 2009, the Tribe opened the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center on purchased land near their ancient settlement of Ha-AH-Poos in West Seattle near the mouth of the Duwamish River. JT told us about Real Rent Duwamish, a grass roots organization that asks people who live and work in Seattle to make rent payments to the Duwamish tribe. The Tribe has yet to be justly compensated for their land, resources and livelihood. All the funds go to Duwamish Tribal Services to support the revival of Duwamish culture.

Duwamish people have been living in the Seattle Metropolitan area for 10,000 years. They were displaced from their homeland by European settlers. The current Duwamish tribe organized in the aftermath of the Treaty of Point Elliott in the 1850s. Although not recognized by the U.S. federal government, the Duwamish remain an organized tribe with roughly 500 enrolled members as of 2004. In 2009, the Tribe opened the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center on purchased land near their ancient settlement of Ha-AH-Poos in West Seattle near the mouth of the Duwamish River. JT told us about Real Rent Duwamish, a grass roots organization that asks people who live and work in Seattle to make rent payments to the Duwamish tribe. The Tribe has yet to be justly compensated for their land, resources and livelihood. All the funds go to Duwamish Tribal Services to support the revival of Duwamish culture.

Further down Yesler Way, JT pointed out the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center. Built in 1915, the building was originally a Jewish synagogue that served the orthodox community. The Central District was largely populated by Jewish people who migrated from Germany and Poland as early as the mid 1800s. African Americans found homes in the Central District and employment in the munitions plants during the war. By the 1970s, the area became the center of the civil rights movement in Seattle. We passed by Edwin Pratt Park which is named in honor of Seattle Urban League director In 1976. Edwin Pratt was murdered by unknown attackers at his home in 1969.

Further down Yesler Way, JT pointed out the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center. Built in 1915, the building was originally a Jewish synagogue that served the orthodox community. The Central District was largely populated by Jewish people who migrated from Germany and Poland as early as the mid 1800s. African Americans found homes in the Central District and employment in the munitions plants during the war. By the 1970s, the area became the center of the civil rights movement in Seattle. We passed by Edwin Pratt Park which is named in honor of Seattle Urban League director In 1976. Edwin Pratt was murdered by unknown attackers at his home in 1969.

Economic forces are driving more neighborhood change. We saw old homes in need of repair and new high density housing developments perched on top of the Yesler “Skid Road.” We walked through the newly enhanced Yesler Community Center taking in great views.

Economic forces are driving more neighborhood change. We saw old homes in need of repair and new high density housing developments perched on top of the Yesler “Skid Road.” We walked through the newly enhanced Yesler Community Center taking in great views.

We crossed the freeway to explore Kobe Terrace Park. Again we observed the interweaving of  Japanese and Chinese culture.

Japanese and Chinese culture.  Cherry and pine trees grow along the terrace pathways alongside the freeway. The trees and a four ton, 200 year old Yukimidoro stone lantern were gifts from Kobe, Seattle’s Japanese sister city. On a sunny day you can enjoy beautiful views of Mt. Rainier from this spot.

Cherry and pine trees grow along the terrace pathways alongside the freeway. The trees and a four ton, 200 year old Yukimidoro stone lantern were gifts from Kobe, Seattle’s Japanese sister city. On a sunny day you can enjoy beautiful views of Mt. Rainier from this spot.

The park incorporates the Danny Woo Community Garden. We observed many folks tending to their small plots of vegetables herbs and flowers here. Another sanctuary place where green life persists surrounded by buildings and concrete.

The park incorporates the Danny Woo Community Garden. We observed many folks tending to their small plots of vegetables herbs and flowers here. Another sanctuary place where green life persists surrounded by buildings and concrete.

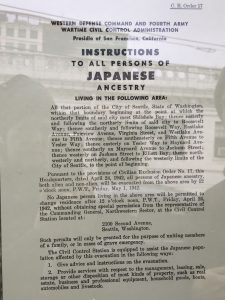

The first wave of Japanese immigration occurred in the 1880s. They faced considerable racism much of which centered around labor. They worked in canneries, railroads and the logging industry. Nevertheless, by the early 1900s they established community and built schools and businesses. The Anti-Japanese League was formed by white business owners in 1919. In response to the 1941 attack on Pearl harbor, ethnic Japanese – including U.S. citizens – were interned in camps: Camp Harmony in Puyallup and Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho. Their lives were uprooted. They lost their belongings, homes and businesses. They were allowed to return after the war finding lodging in churches and the Seattle Japanese Language School building.  JT guided us through the Panama Hotel. It was built in 1910 by the first Japanese-American architect in Seattle, Sabro Ozasa. It contains the last remaining Japanese bathhouse in the United States. The building housed businesses, restaurants, and sleeping quarters for residents and visitors.

JT guided us through the Panama Hotel. It was built in 1910 by the first Japanese-American architect in Seattle, Sabro Ozasa. It contains the last remaining Japanese bathhouse in the United States. The building housed businesses, restaurants, and sleeping quarters for residents and visitors.

Jan Johnson, the third owner, restored the building to reflect its original condition before the Japanese evacuation. Today, you can see the old belongs left behind by Japanese families through a glass panel in the floorboards.

Chinese people were the first Asians to settle in Seattle in the 1860s. They worked as fishermen, cannery and mill workers, miners, loggers and later on railroad and building construction projects. Their arrival was welcome but eventually resentment grew as more white settlers arrived and competed for work. This resentment was felt in other developing states and led to the passage of the federal Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. They initially settled around Pioneer Square. By the 1930s Chinatown and Japan Town were established neighborhoods. In the 1930s, the Chinese American community united with the Japanese American and Filipino American communities to fight a proposed ban on interracial marriage. In 1951 the area was renamed the Seattle Chinatown-International District. In 2011 Gary Locke became the first governor in the continental United States of Asian descent, and is the only Chinese American ever to have served as a governor of any state.

We wound our way down to King St. and walked through Hing Hay Park just up the street from the Harbor City Restaurant and the Wing Luke Asian Museum. We joined a crowd of hungry Dim Sum fans waiting for a table in the rain. Hungry faces reflected the growing diversity of Seattle. How did all these different people get here? As in the past, many people come here seeking opportunity and many come for sanctuary. In her Washington Post editorial message, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan wrote: “Seattle is not afraid of immigrants and refugees. In fact, we have always welcomed people who have faced tremendous hardships around the world. Immigrants and refugees are part of Seattle’s heritage, and they will continue to make us the city of the future. . . . In Seattle, we know that our immigrant and refugee communities make our city a stronger, more vibrant place. Our immigrant neighbors make up more than 18 percent of our population, and 21 percent of our population speaks a language other than English at home. They create businesses and jobs. They create art and culture. They help teach our kids, serve in law enforcement and the military, and lead our places of faith.”

We wound our way down to King St. and walked through Hing Hay Park just up the street from the Harbor City Restaurant and the Wing Luke Asian Museum. We joined a crowd of hungry Dim Sum fans waiting for a table in the rain. Hungry faces reflected the growing diversity of Seattle. How did all these different people get here? As in the past, many people come here seeking opportunity and many come for sanctuary. In her Washington Post editorial message, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan wrote: “Seattle is not afraid of immigrants and refugees. In fact, we have always welcomed people who have faced tremendous hardships around the world. Immigrants and refugees are part of Seattle’s heritage, and they will continue to make us the city of the future. . . . In Seattle, we know that our immigrant and refugee communities make our city a stronger, more vibrant place. Our immigrant neighbors make up more than 18 percent of our population, and 21 percent of our population speaks a language other than English at home. They create businesses and jobs. They create art and culture. They help teach our kids, serve in law enforcement and the military, and lead our places of faith.”

In gardening terminology, a volunteer is a plant that grows on its own, rather than being planted by a gardener. Volunteers often grow from seeds that float in on the wind, are dropped by the birds, animals or compost. Volunteers enrich our gardens and promote diversity. I hope Mayor Durkan will fulfill her promise to welcome immigrant families and the cultural gifts they bring. Studying ethnobotany has enriched my life immeasurably. Thanks to gifted teachers, I’ve learned to recognize the incredible value in native and wild plants including simple weeds.

In gardening terminology, a volunteer is a plant that grows on its own, rather than being planted by a gardener. Volunteers often grow from seeds that float in on the wind, are dropped by the birds, animals or compost. Volunteers enrich our gardens and promote diversity. I hope Mayor Durkan will fulfill her promise to welcome immigrant families and the cultural gifts they bring. Studying ethnobotany has enriched my life immeasurably. Thanks to gifted teachers, I’ve learned to recognize the incredible value in native and wild plants including simple weeds.